Throughout history, buildings and cities have stood as a representation of human society, reflecting the values, triumphs, and eventual fall of civilisations over the course of time. Those who design and build the physical environments in which we live — architects, engineers, and planners — do more than just provide shelter for people to live and work. They envision how our surroundings should look and feel, and by default shape society.

“Architecture has always dealt with the gritty problems of here and now,” says Hanif Kara, who sits at the nexus of these separate yet related realms. “It impacts our lives deeply and daily.”

A civil structural engineer by discipline, with an eye for the broader aspects like aesthetics of architecture, Hanif has been uniquely positioned to make valuable contributions to both disciplines. He defines himself as a ‘design engineer,’ someone who understands both the construction of safe structures and the value of design and form.

His contributions have been recognised at the highest levels. Last month he was awarded an OBE in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours List for his services to architecture, engineering, and education. How did it feel to receive this honour? “I was overwhelmed with joy,” said Hanif, “and am grateful to all the people that have supported me over the years.”

Being well-respected in his field and beyond, Hanif is no stranger to awards and prizes, but this one was different. “Recognition in one’s own field is one thing,” he says, “but to get national recognition in the three domains of architecture, engineering, and education has deeper meaning so is very satisfying. I hope it inspires others to enter these important fields which affect all our lives.“

A pioneering firm

As design director and co-founder of AKT II, a structural engineering firm based in London, Hanif has collaborated with some of the world’s leading architects — including Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, Herzog & de Meuron, Farshid Moussavi, and David Chipperfield — on a number of pioneering projects.

Having been in operation for 25 years now, AKT II has gained a significant international reputation, attracting talent from across the globe. Despite employing 350 staff, Hanif is still actively involved in the various projects the company juggles: “We have mastered a process that keeps me hands-on,” he says.

The team counts approximately 100 current projects at different stages of design or construction — an astonishing amount in any industry. These range from “large residential buildings; cultural projects; headquarters for Google and Apple; laboratories; and so on.”

“Recently, we won the competition to design the Noida Airport in Delhi and just started construction of a National Cathedral in Accra, whilst we are opening the Grand Theatre of Rabat in Morocco in the coming weeks.”

Under his design leadership, the practice has won over 350 design awards, including the RIBA Stirling Prize on four separate occasions.

All this is in addition to teaching at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, where Hanif has served as a Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology for the past 15 years. In their classes, students are taught how to solve the problems facing the built environment today and in the future. In the process, he has been recognised for linking design, research, education, and practice.

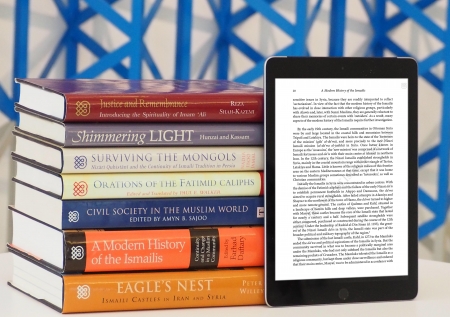

These qualities and experiences have come in handy for the Imamat and AKDN projects that Hanif has contributed to, including most recently the Ismaili Center in Houston — which, similar to many of his collaborations, was an international design competition win — and the Aga Khan Academy in Dhaka. Since 2004, he has been involved with the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, considered one of the most renowned and prestigious awards of its kind.

HKara

Aga Khan Award for Architecture

Have his experiences with the Award changed how he engages with architecture? “Absolutely and profoundly so,” Hanif affirms. The Award’s Master Jury and Steering Group members come from a pool of the most talented thought leaders from a variety of disciplines. Being immersed in such circles, one cannot help but be positively influenced and motivated.

“As the first engineer in that environment, I have learnt a lot and re-calibrated what I do in design practice but also what I teach.”

The Award plays an important role in influencing global architectural discourse and promoting innovative solutions to problems faced by many societies. The idea is that advocates go out and spread what the experience has taught them, while the nominated projects themselves are held up as examples for replication.

“I have often reminded colleagues that its 40+ year history has lasted longer than many of the buildings we see around us,” Hanif says. “During this time, it has built a tremendous knowledge bank for the whole world to access like no other.”

This body of knowledge is often accessed by urban planners, practitioners, and teachers when thinking of new projects, policies, and construction methods, with the intention of solving problems and improving the whole architectural process, from initial drawings to completion.

Since its inception, the Aga Khan Award has championed many of the concerns that are now common today, such as sustainability, human scale, climate adaptation, and quality of life. Reflecting on the Award’s impact since he established it in 1977, Mawlana Hazar Imam said in 2001 that, “The Award has become a sophisticated observer of physical change in civil society.”

Building the future

Most would agree that the pace of this change has accelerated since the Award’s most recent cycle in 2019. Like everything else, the Covid-19 pandemic has impacted the theory and practice of designing buildings and cities. Lockdowns brought inequalities into sharp focus - some were fortunate to have outdoor spaces and multiple rooms to isolate in, while others had to make do with much less.

“On the one hand, we have learnt the importance of architecture through a closer reading of our homes and workplaces,” Hanif says about the pandemic, “but equally, we have more appreciation for the value of nature and the infrastructure that inhabits it.”

Every major pandemic in history has resulted in a large-scale architectural change. Architects and Engineers have begun exploring solutions for post-Covid urban development with multifunctional spaces, open streets, and healthy communities at the centre of their thinking.

This is all while the climate crisis is becoming a more prominent influence on the industry. Those involved in urban planning and construction have the task of converting sustainability from a buzzword into a principle of design.

Yet, times of crises have often brought about change and innovation. So how might cities evolve in the coming decade? “We see a trend away from chasing square footage and size and an attraction to better-designed buildings,” Hanif says.

Both theorists and practitioners are looking at how buildings can work better for humans and the planet, including blurring the line between indoor and outdoor spaces, green roofs, rainwater recycling, solar walls and windows, and so-called ‘smart homes.’

In his professional career, Hanif continues to push the boundaries of what he calls ‘bigger projects:’ researching and practising sustainable construction methods; new computational tools to help design a better world; and using materials in productive ways to make advances in his work. The years ahead sound promising.

“Covid has given us all the time to step back and find new springboards for the future,” he says, “and I am fortunate to be surfing the frontline of that wave.”